Just about everyone uses “agile” or “lean” in describing their business these days, but very few people actually use the terms in ways that embody their real meaning. And, while it may help with marketing, if you say you’re running lean, and you’re not actually practicing the discipline, consider yourself warned. Project and product management methodologies are disciplines, and they require rigor and practice in order for your company to reap the benefits. As a certified SCRUM Master, I take my disciplines seriously. But this is as a result of surviving the kind of cautionary tales one hopes only to read about in glib blog posts. And I hope this primer helps you avoid some of the pitfalls to which I was exposed.

Let’s start by imagining a scenario. You’re in New York City, and you’re craving a unique dining experience. You’ve heard about a place up in Boston, but you’re not sure if it’s really what you’re looking for, even though you’ve researched whatever you could about it. And, if you want to go up there, you’ll need to commit. That means, get on the freeway or hop on a train, and head straight there. The only drawback is that you might arrive and find it’s not at all what you imagined. Then your investment in the journey is a waste, and you have little choice but to go back and start researching again to find a better fit.

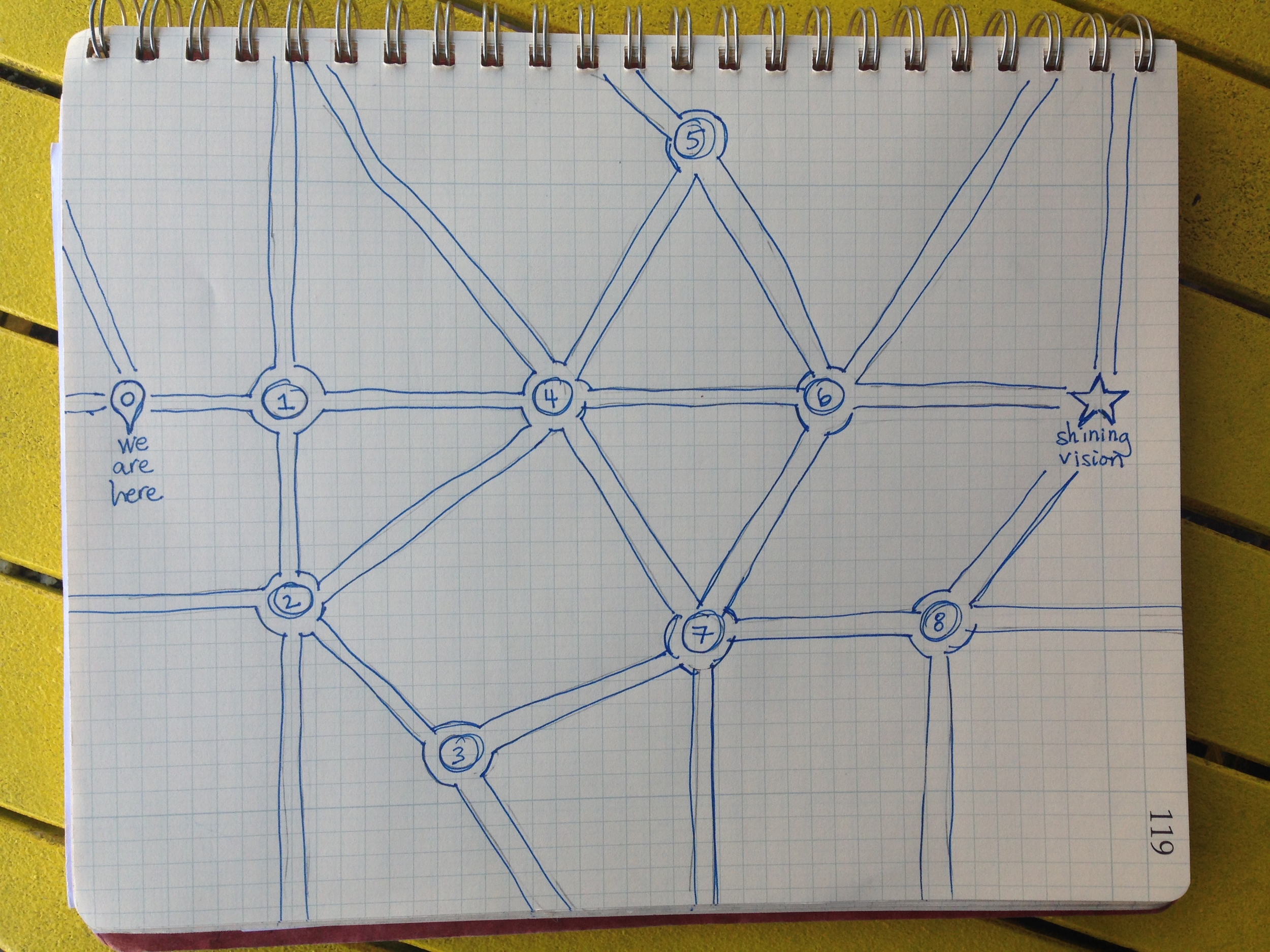

MVP of a Curious Catalyst Opportunity Map

However, if you were to hop in the car and drive to your current favorite restaurant and ask them where you should go, they’ll probably have a recommendation closer and one that’s more inline with your vibe, as you have some shared criteria. And even if you drive a short distance more, only to find it’s not your cup of tea, you’d get another recommendation and more information about what you actually thought you wanted, so that you can make a better decision over time. This loosely speaks to the assumptions underlying both agile and lean methodologies: that shorter bursts of activity, with built in feedback loops, for gathering user insights and refining the offering, will ultimately lead to a more satisfying outcome. Note that I didn’t say less expensive, and this is one of the most misunderstood principles when deciding which development approach is right for you and your company.

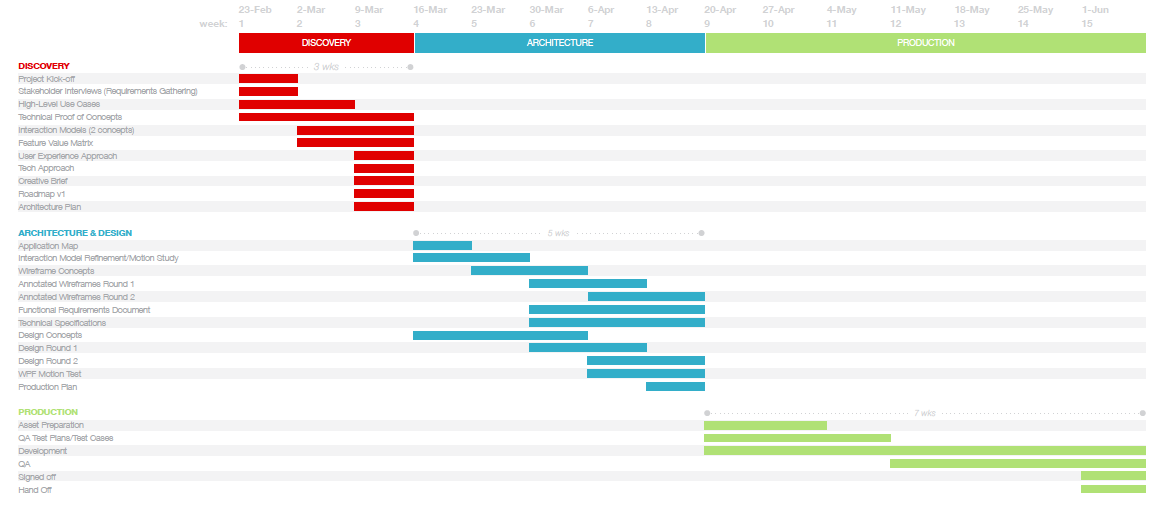

But let’s begin by clarifying a few terms. Traditional product development is called “waterfall” because when you plot sequential design with dependencies, progress looks as though it flows down from step to step over time. This practice developed in manufacturing and construction industries, where there is a clear case to be made for building the framing of the house before you can proceed to painting the walls. It also should be obvious that in waterfall projects, if you have changes to requirements mid-way through the process, the cost will be exorbitant. For example, if you’ve built a house, put tiles in, and decide to change the entire shape of the kitchen, you can do it, but you can be sure you’ll pay for it. The key assumption here is that you never proceed to the next step until the previous one is complete. And, from a team planning standpoint, resources with different skill sets can roll on and off the project as needed.

A traditional waterfall project plan often called a Gantt Chart

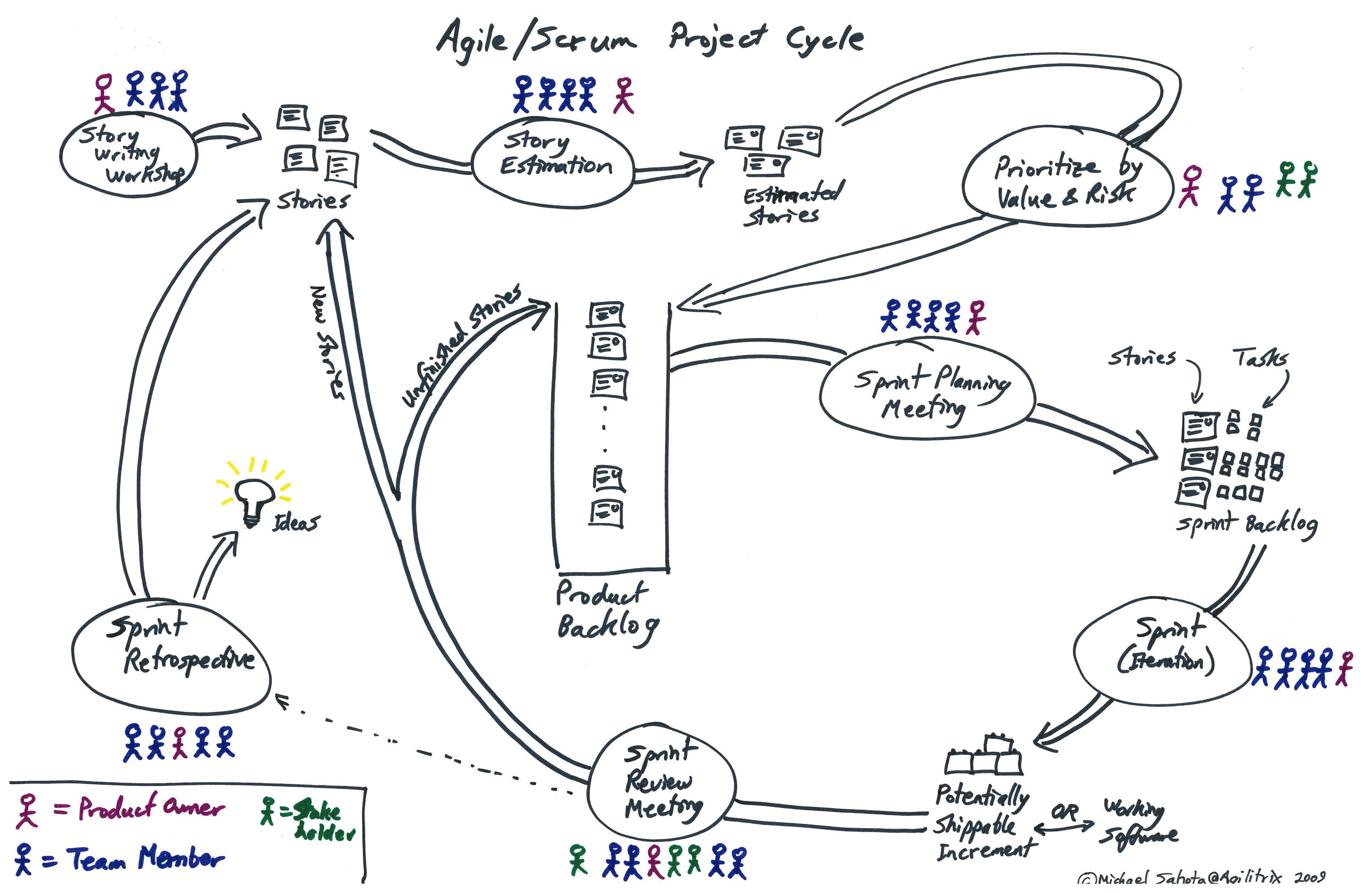

During the early heydays of digital agencies, the idea of “agile” entered the lexicon as the new way to save costs and push the boundaries of technical innovation and development. As one of the most widely adopted flavors of agile, Scrum was first defined as "a flexible, holistic product development strategy where a development team works as a unit to reach a common goal" as opposed to a "traditional, sequential approach" in 1986 by Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka in the "New New Product Development Game." They claimed this approach would increase speed and flexibility, based on case studies from manufacturing firms in the automotive, photocopier and printer industries; and they called this the holistic or rugby approach, as the whole process is performed by one cross-functional team across multiple overlapping phases, where the team "tries to go the distance as a unit, passing the ball back and forth."

More recently, in 2011, Eric Reis coined the now frequently used term the “lean startup” to describe a method for developing business and products in shorter cycles. Central to his approach is what he calls “validated learning” – or a combination of business-hypothesis-driven experimentation and iterative releases. Ries' overall claim is that if startups invest their time into incrementally building products or services to meet the needs of early customers, they can reduce the market risks and sidestep the need for large amounts of initial project funding and expensive product launches and failures. The art of doing this well is in knowing how to define the fundamental unit of testing, which Reis calls the “Minimum Viable Product” or MVP. As I am known to say, this can be half a product but it can never be a half-baked product. And, at best, the MVP captures the core value and biggest user need, so that the product grows organically out of a truly human-centered solution.

Generally, both agile and lean methodologies put primacy on rapid iterative and incremental design with a dedicated, self-organizing, multi-disciplinary team. The requirements and solutions then evolve over a time-boxed period of intense effort called a “sprint” with well-defined tasks. In both cases, estimation, storytelling, frequent communication and reporting are critical for success - and this skill set is as much art as it is science. With daily check-ins, teams can immediately and flexibly respond to issues, changes, or discoveries, before getting too far along. And by being clear about actionable metrics and a backlog of additional features, all team stakeholders can make clear, informed decisions at critical moments before deciding to push on or pivot the product.

A great capture of the SCRUM cycle courtesy of Agilitrix.com

As you look to evaluate vendors or consider putting one of these disciplines into practice, beware the jargon and look for experience, which probably comes from emerging technology, mid-stage startups or the rare intrapreneur with a mandate to experiment. More than anything, agile and lean practices produce artifacts of directed thinking and prototyping, user feedback and guideposts to the next sprint.

At Curious Catalyst, we expand on the Opportunity Map sketch you see above as the key deliverable coming out of Discovery and Visioning sprints. Each “roundabout” represents a critical assumption and a potential area for investigation. And, depending on what we find during a given sprint, we may continue on in the direction we were going to prototype, or we may recommend changes to the strategy behind the solution we’ll test next. This allows us to remain responsive to rapidly changing market demands, to leverage new insights in real time, and to demonstrate traction after mere weeks instead of years. Let's take the example of our foray into using re-imagined food trucks to mitigate the complexities of food deserts. In this case, we should start with the most obvious assumption, which is that people will buy food (produce, prepared food, frozen food) off of trucks. If that isn't proven to be true by our group of citizen stakeholders, it would be a waste of time for us to investigate and prototype solutions around mobile recipes and grab-and-go dinners.

When tackling the increasingly complex challenges that our urban centers are facing, we believe an approach combining agile and lean methodologies is the only way forward – for harnessing broader expertise, wisely allocating limited funds, and building a tangible vision for change that can be implemented sprint by sprint.